- Architect: P.A.C

- Location: Ladakh, India

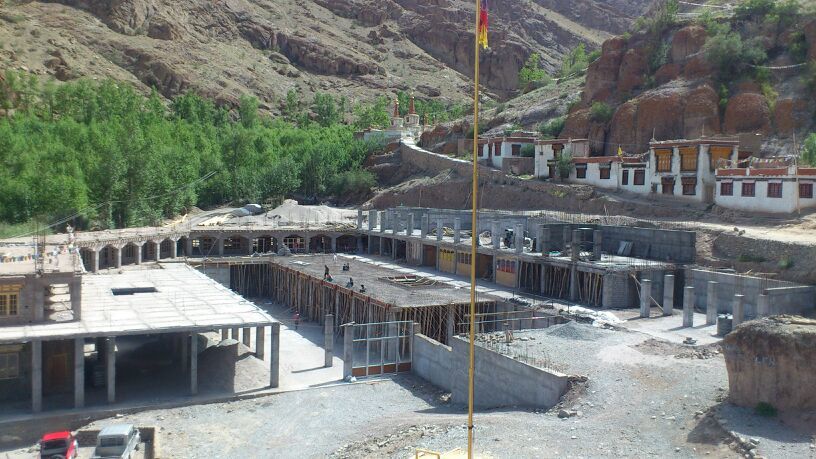

- Client: Hemis Monastery

Designing and building the Hemis Monastic School has been a once in a lifetime project that has taken ten years (so far) and has rewritten the rules for large timber structures in the developing world. From the time we were first appointed to the project it has been subject to every imaginable impediment, from extreme weather, earthquake events, floods, political upheavals and an ever evolving set of design responses to suit the ever evolving circumstances.

The Story

In June 2007, Packman Lucas were instructed on the design and procurement of the Baden Powell Scouting Centre on Brownsea Island, in Poole Harbour. Brownsea Island has been an isolated and closely monitored wildlife haven where little or no influences from the mainland have been allowed to impact on its ecosystem. There is a thriving population of red squirrels; ferns, flowers fungi and lichens; trees that have been endangered elsewhere in the UK and so many other sensitive and precious aspects of wild life that receive the most stringent protection from a number of important bodies. The decision to permit the existing scouting centre to be demolished and replaced in its entirety was taken after many years of careful deliberation.

The original scouting centre was a collection of portakabins and steel containers that were run down and barely capable of fulfilling their purpose. Not surprising that the proposed development was required to be an exemplar of sustainable, energy efficient, low impact architecture that would take its energy from sustainable sources. We worked with Wilkinson King – the appointed architects – and XCO2 – the energy consultants - to produce a set of proposals that fulfilled these requirements. Almost as a by-product, the development proved to be an exquisite example of simple regeneration that was hailed at the time for its apparently simple set of solutions to the whole family of issues that it was designed to address. Not surprising it has been recognised as an exemplar of how to create architecture in the most sensitive of locations and has received many awards, and a good deal of international exposure.

At the same time we were beginning our work on Brownsea Island, the Buddhist Shambunath Institute of Nepal were beginning the construction of a new monastic School at Hemis Monastery in Northern Ladakh. The spiritual leader of the order is His Holiness the Twelfth Gyalwang Drukpa. He had a vision for a new residential school for 500 trainee monks to be set alongside the historic Hemis Monastery at an altitude of 13,000ft in the Himalayas. Originally dating from the 11th century, the existing monastery was built in 1672 using the traditional timber, stone and mud bricks that form the basis of the vernacular construction throughout Ladakh. His Holiness required the new monastic school to be in the form of a serpent – a floor plan that snaked across the mountain in a series of loops. The construction team began work on the project, but it did not have the benefit of a set of designs, or an experienced designer to direct operations. After two years of endeavour, the team conceded that they had insufficient experience to take the project any further, and a major rethink began. Zangmo Li Lian Teh, a senior member of the Shambunath organisation, consulted her son Keong – a young architect with a practice in Singapore. Keong immediately realised that there were some fundamental problems with the existing design and began to analyse how they might be resolved. As luck would have it, Keong had recently heard of the Brownsea Island project through the energy consultants XCo2 and so he made contact with the team. Some weeks later we visited the site to begin to understand the issues in play.

Construction

We were initially slightly overwhelmed with the magnitude of the project, and in awe of the determination of the incumbent team and their efforts to date, but it was apparent that not a great deal of what had been done could be carried forward.

As a general rule, buildings for cold climates will perform better

thermally if the ratio of internal volume to external surface area can

be as large as possible. The serpent form was the very opposite of this;

a long snaking, linear building with extremely large external surfaces

with the potential for massive heat loss.

At the time of our

first visit the whole site was bleak and desolate and covered in snow.

Those elements that had been constructed were primarily of poor quality

concrete and an apparently random form. There were no drawings for the

project.

Our first decision was to absorb what had been built into a generally

cuboid form and to begin to address the issue of how to trap whatever

sunshine might be available, and to improve its overall heat retention

capability.

The indigenous materials of the region are Himalayan

granite, high altitude Poplar trees and Willow. Local construction also

relies heavily on mud bricks. The more important buildings also make

good use of large timber baulks in a simple, Escher-like configurations.

These can only be sourced from Kashmir, to the North.

Materials

Despite being in a highly seismic region, Hemis Monastery has survived for 350 years with relatively little seismic damage. The local team, in spite of their natural courtesy, were slightly incredulous at our decision to design the new school as an earthquake-resistant structure. ‘We do not have earthquakes here’. ‘Our parents, grandparents and great-grand parents have never experienced an earthquake’. In examining the records for the region there is some truth in this, but at 13,000ft in the Himalayas we could not, with a clear conscience, ignore the risk.

On this basis we established the initial structural parameters that would be used in the design of the school. These were as follows:

- The overall cuboid form would be surrounded with a reinforced concrete perimeter frame that will provide the principal resistance to earthquake forces.

- The internal structure will be an arrangement of beams, spreaders and columns of traditional Ladakhi form.

- The internal framework will be fitted with diagonal steel bracing, in the plane of the floors, which is tied to the perimeter concrete structure.

- Floor construction will be traditional poplar logs as floor joists, willow pollards will bridge the poplar logs, grass will top off the willow and the floor will be made from compacted mud above the grass.

- Roof construction will be as floor construction.

- Three large atria will run from ground floor to roof with a fully glazed roof and end walls to form the key solar collection measures.

- External elevations will be fully glazed, but with two different forms of glazing, namely Trombe walls and fully glazed windows.

- Classrooms will have fully double glazed elevations to permit the quickest possible warm up period each morning.

- Bedrooms will have trombe walls with a small window at their centre. These will permit a slow warming through the day and a retention of heat through the night.

The task for the architectural team was to take this fairly rigorous form and create the rooms, spaces and circulation patterns that will allow it to fulfil its functions.

The incumbent team had established two key teams of workers for the project. The stonemasons were exclusively Nepali, and very skilful. The carpenters were exclusively Indian and also very skilled, but with little experience of the form of construction that we were proposing. We were able to establish an arrangement for the whole of the building in a matter of weeks, and this allowed the site team to begin excavating and constructing the foundations. Once the foundations were complete we were able to begin the process of constructing the reinforced concrete elements of the building, and this required a quantum leap in the quality of concrete work that we required for the building to work properly. What followed was a dramatic improvement in the whole matter of cutting and bending steel reinforcement, constructing timber shutters and the process of mixing and placing concrete. The new, and higher, skill levels that grew out of this process allowed us to be more adventurous with our designs, and this in turn led to an evolution of the design that led to more dramatic internal geometry. One of the key client requirements was a major prayer hall at ground level, and this had been within one of the atria. This relegated the other two atria to a more subordinate role, and to an extent divided the ground floor in a less than satisfactory way. Given the rapidly rising skill levels on site, we made the decision to re-orientate the prayer hall at ground level to be perpendicular to the atria. This made a dramatic improvement to the diagram, giving all atria a relationship with the prayer hall and transforming it into the heart of the building. The down side was that it required us to configure a long span ‘roof’ to the prayer hall that would be capable of carrying the upper storeys at its mid-point. This was achieved by building massive timber pitched trusses from an amalgamation of timber baulks and tying their bearing points across the space with 40mm steel bars - normally used for reinforcing concrete. The nett effect of this is spectacular.

Progress to Date

The building is now in its tenth year of construction. The original

contract period was hoped to be three years, but this was hopelessly

optimistic. Work in springtime cannot begin until the pass is cleared of

snow. Only then can the Nepalese make their way to site and deliveries

of the bulk building materials resume. The political problems in Kashmir

have on occasions stopped the supply of the timber baulks. The weather

can sometimes close in and make work on site extremely slow. The

disastrous floods in Kashmir in September 2014 caused major loss of life

and disrupted the whole country for several months. Our timber supplier

was located on the bank of a major river, and our delivery for the year

was assembled there ready for shipment when the floods struck. All of

our timber was washed away, and we gave up hope of any further work for

the year. However, the timber merchant is a resourceful man and he led a

team of his workers downstream and, bit by bit, recovered most of our

order and was able to ship it in a matter of weeks.

At the time

of writing – January 2019 – we have now completed the roof construction

and we are making preparations to return to site to begin the task of

constructing the three spectacular glazed timber roofs that will top off

the three atria.

Timeline

2012

Ground floor slab, retaining walls and columns cast. Fixing reinforcement and pouring the base of the 10m high retaining wall that forms the basis of the 'survival' core of the school. Note how the Nepali mothers still care for their children whilst working, with the tiniest infants snuggled into hammocks hung between columns.

2020

Hand-over anticipated during 2020. Check back soon for details!